It’s been five decades to the day since 25,000 people arrived in the Alabama’s capitol to demand the right to vote for African-Americans. They had marched 50 miles from Selma to Montgomery, but might never have had the chance to do so if not for Judge Frank Johnson, Jr. This is the story of one man’s lasting effect on American civil rights.

Today, John Loss is an attorney in Buffalo. But in 1987 he served as a law clerk for Judge Frank Johnson, Jr.

“He was a man who I consider to be the greatest American living hero at the time,” Loss remarked.

Johnson was appointed as a Federal District Court Judge in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955. At age 37, he was the youngest federal judge in the country, surrounded by a culture of segregation.

“Everybody in the courtroom no matter what their race was, no matter what their background was deserved respect,” John Loss, Attorney.

Johnson liked to tell the story of his ancestors’ secession from Alabama during the civil war. They lived in the popularly known, “Free State of Winston,” a pro-union county. Loss says that background was the foundation of Johnson’s career.

“That carried with him his entire judicial career, that he wasn’t going to be swayed by what other people thought, but he was going to do what was right and what was just,” said Loss.

On the federal bench, Johnson quickly got his feet wet. His first case was a panel decision which said Rosa Parks did not have to sit at the back of the bus.

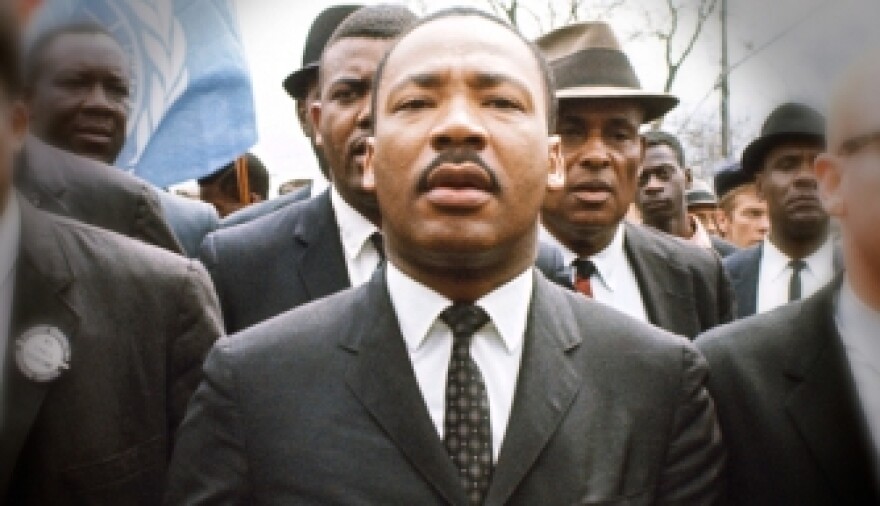

Ten years later, after “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Alabama, Johnson issued an injunction against further marches. He held a four and a half day hearing, with speakers like Martin Luther King, Jr., to determine whether demonstrators would be permitted to march on the federal highway to Montgomery.

Loss says what was important to Johnson wasn’t how history would judge his actions, but rather what was right at the time. When state attorneys were rude to African Americans during the hearings, Loss says Johnson scolded them openly.

“Everybody in the courtroom no matter what their race was, no matter what their background was deserved respect,” Loss recalled, “And that attorney thereafter then towed the line.”

It was a turning point in the civil rights movement, and a prime example of his objectivity and temperate personality.

“He never saw it as something that was going to be historic,” Loss said of Johnson’s view of the hearing. “He just saw it as the case in front of him and applied the law as he saw it, and permitted the march to occur."

This year, John Loss followed in the footsteps of civil rights leaders and walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. He was reminded that it’s named for the Confederate General who was a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan – a structural tribute to white supremacy. Loss says the experience was sobering, and took on a sense of irony.

“The week after I walked over that very bridge, President Obama – the first African-American President – fifty years to the day after Bloody Sunday was there on the bridge named for the bigot. But there he was, the African-American President,” said Loss.

The kinds of events that took place in Selma aren’t likely to happen in the same way today, says Loss. Partly because back then, only three television networks garnered the nation’s attention, keeping them focused on the issue.

“So people were just transfixed by what was happening, by the powerful visual images,” Loss said.

Loss says the sadder reason is that protesting on government property – which includes roads like Route 80 to Montgomery – is now prohibited. He says times are much better now, but there’s still work to be done.

Judge Frank Johnson, Jr. received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton on September 29, 2995. He died four years later at the age of 80, but his legacy lives on in the civil rights landscape of today. One of the phrases, Loss says the judge always liked to say continues to ring true.

“The hallmark of any society that claims to be civilized has to be precisely its ability to do justice, and that’s what Judge Johnson did throughout his 40-year career.”

Judge Johnson’s legal papers were donated to library of congress in 1991. Information on how to access them is available here.